|

207 SQUADRON ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORYWhyte Crew, Lancaster L7547 EM-M

|

|

The Milan Raid of 14/15 February 1943 involved 142 Lancasters of 1, 5 and 8 Groups which carried out concentrated bombing in good visibility. Fires could be seen from 100 miles away on the return flight. No report is available from Milan. Italian defences were usually weak and only 2 Lancasters were lost on this raid. The quantity of bombs carried by Bomber Command so far in the war reached 100,000 tones during this operation. (Bomber Command War Diaries, Middlebrook & Everitt).

207 Squadron, then at RAF Langar, tasked 9 aircraft for this raid of which 3 failed to complete the mission. L7547 EM-M was the only 207 Sqn casualty.

The explanation [provided by Raymond Glynne-Owen] for the three aircraft not completing the operation is that on the previous raid on 13/14th February (to Lorient) five of 207's aircraft are shown in the Langar Raid Book as having landed at Bottesford, including F/Sgt Whyte in L7547/M.

For the raid on the 14/15th February three of 207's 9 aircraft taking part took off from Bottesford, including Whyte in L7547/M. A resident 467 Sqn Lancaster then bogged and blocked the Bottesford runway, preventing two more of 207's aircraft from taking off plus another of 207's Lancs had a defective exhaust valve which scrubbed that aircraft at Bottesford.

In his evasion report (WO208/3318 SPG1768) John Whyte said " We took off from RAF Bottesford at about 1900 hours on 14 Feb 43 in a Lancaster aircraft to bomb Milan. We reached our target. On the way home (probably about 2330 hrs) the port outer engine caught fire. The wing was set on fire immediately after. We dived down and tried, unsuccessfully, to put out the fire. I do not know the cause of the fire.

I came down about midnight in hilly country near St Brisson. After hiding my parachute and flying kit I started walking and about two hours later I met my flight engineer Sgt Eyre. We went into some woods and hid for the remainder of that night.

The next morning we met two Spaniards on the road and asked them for help, but they could not do anything for us. A little later we came across another Spaniard burning charcoal in the woods. He took us to see a Frenchman, who in turn took us to a house on the outskirts of St Brisson. We spent two or three days here and from this point our journey was arranged for us."

In his report (WO208/3318 SPG1783) Stan Eyre says "I was a member of the same crew as F/Sgt Whyte. I came down near St Brisson. After burying my parachute and flying kit I started walking and about two hours later I met F/Sgt Whyte and the remainder of my journey to Switzerland is as related in his report. I heard later that at St Brisson that five airmen had been found dead in an aircraft on the day that we had crashed. They were buried in the village, and I believe them to have been the remaining members of our crew."

The five members of the crew who died when the aircraft crashed are buried in St. Brisson, which according to the CWGC is a village and commune, in the Department of the Cote-d'Or, 75 kilometres north-east of Nevers and 11 kilometres west of Saulieu. The village is south of the main road from Saulieu to Lormes. The cemetery is south-west of the village, on the road to Le Vernay. The graves are to be found south-west of the entrance, in the far corner.

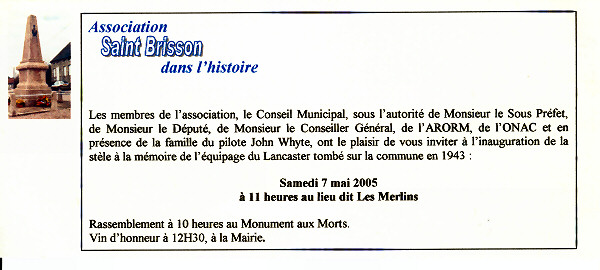

Georges Pillot wrote to the editor on 16 May 2005: "The memorial stone to the Whyte crew has been inaugurated in the presence of the Whyte family - Mary, John and Christopher, on Saturday May 7th 2005. I managed to get flowers with poppies to go with the memorial text you provided.

It was a great ceremony, for our little village of 280 people, there were more than a hundred to commemorate this 207 Squadron crew.

The Representative of the Departement and a Member of Parliament joined

us, as well as veterans.

As you can see on the photographs there were flowers, people, officials,

and flags, and great emotion.

After the ceremony, in the Council House, people visited an exhibition

about L7547 made by our association.

The following day, May 8th 2005, the official ceremony of the end of the war, the Whyte family laid a rose on the grave each of the 5 airmen killed in the crash.

I thank you very much for the help you gave us for this memorial. I am still finding other more information about this crash and the evasion of Stanley Eyre and John Whyte."

images - (source Pillot) |

|

?? reads the dedication (source Pillot)

|

A l'équipage du Lancaster L.7547. tombé le 15/02/1943

|

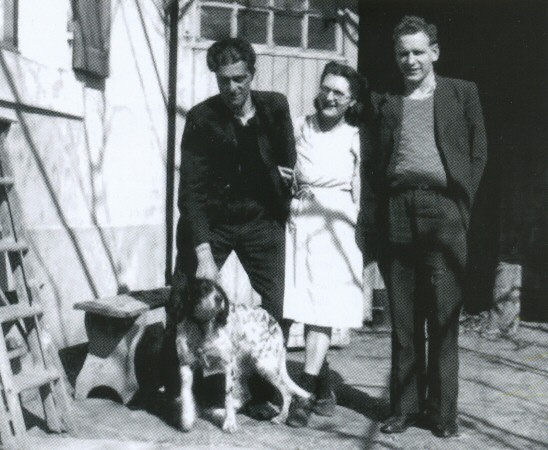

Christopher Whyte, Mary Whyte and John Whyte,

the son of John HF Whyte, pilot of EM-M L7547 (source Pillot)

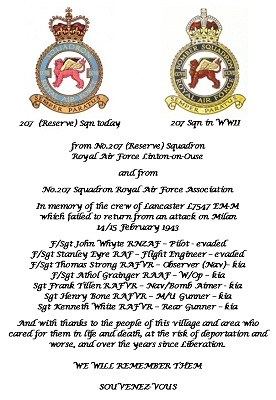

tribute from No.207(R) Squadron and No.207 Sqn RAF Association (source Pillot) |

text of the tribute *see below regarding roles |

The following message was sent for the dedication of the Memorial on behalf of Wg Cdr Ken Marwood AFC RAF(Retd), President of the 207 Squadron RAF Association and Sqn Ldr Paul Stockley RAF, Officer Commanding No.207 (Reserve) Squadron RAF Linton on Ouse (Sqn Ldr Stockley, like John Whyte, is a New Zealander):

“We are very grateful to all who have worked to establish the memorial to the crew of Lancaster EM-M L7547. They are among those who failed to return from operations when serving on No.207 Squadron in World War II in the cause of freedom: 955 who were killed, 171 taken prisoner and 39 who though shot down evaded capture.

We would have like to have joined in your ceremonies. This weekend a group from the Association is attending the dedication of a memorial in Belgium and visiting cemeteries there where several of our crews are buried. We are with you in spirit.

We also honour those from the village and the locality who because of their love of liberty and care of Allied airmen in life and death, suffered under the Nazi yoke. And we thank those who over the long years since the end of the War, have kept alive the memory of those who did not return to their homes here or in the Commonwealth."

"God Save the Queen. Vive la France. Long live Liberty. ”

On May 8 2005 Christopher Whyte, grandson of the pilot,

lays a rose at the grave of one of those killed in the crew (source

Pillot)

The stone in front of the headstones reads "Souvenir des FFI à leurs

camarades Anglais, morts pour la Liberté"

On May 8 2005, the 60th anniversary of VE Day, a rose was laid by the

Whyte family

at each grave of the five who died and who now lie in the Communal

Cemetery, Saint Brisson

[Sgt Tillen's grave not in this photo] (source Pillot)

WHYTE, John Henry Francis F/Sgt RNZAF NZ412522 Pilot -

Evaded

EYRE, Stanley Herbert Kitchener F/Sgt RAF 650325 Flight Engineer -

Evaded

TILLEN, Frank Ivan Sgt RAFVR 1175445 Navigator/B - Killed 15-Feb-43

STRONG, Thomas William Kitchener F/Sgt RAFVR 1114468 Obs/Bomb Aimer 1-

Killed 15-Feb-43

GRAINGER, Athol Richard F/Sgt RAAF A/403169 Wireless Op/AG - Killed

15-Feb-43

BONE, Henry George Sgt RAFVR 1381738 Air Gunner (MU) - Killed 15-Feb-43

WHITE, Kenneth Sgt RAFVR 1535795 Air Gunner (R) - Killed 15-Feb-43

The five graves including Sgt Frank Tillen, at a previous ceremony (source

Pillot)

24 Oct 2005 - Robin Eyre, Stanley Eyre's son, makes contact seeking information about his father's escape from St Brisson to Switzerland. From documents found in his mother's house after she died in August 2003 he knows that his father stayed in Faverges and Annecy in March 1943 before travelling to Switzerland. In October 1943 his mother received a telegram to say he was safe in Berne. Stanley Eyre retired from the RAF with the rank of Squadron Leader and was awarded the MBE and DFC.

John and Mary Whyte examining a display of wreckage fragments |

John Whyte writes

26 Oct 2005: [edited] In 2003 I made my first visit to St

Brisson in France but we did not learn a lot as we lacked

contacts at that time and could only spend one day there. We

visited the cemetery and the five graves and visited the Museum

of Resistance.

I was very pleased to hear that contact has been made with Robin Eyre, but wish it could have been in time for the commemoration in France last May. It was a extremely moving occasion and the French people were extremely good to us. Mary my wife and I stayed five days with Georges Pillot and our son Chris came from London where he lives to join us for three of those days. Our visit seemed to bring out stories from the local French

people and now, with Georges and Philippe [Senac] , we are

still learning more. I have many of photos and notes from

those five days as memories. |

They are the only things from the war that he ever displayed. In fact I remember being in trouble as a boy was when he caught me looking at his DFC, which I found hidden in the back of a cabinet. He did not speak about the war at all.

I also have in my possession his Flying Log and a diary he kept in Switzerland while he was there.

Thank you for being able to lay the wreath on behalf of 207 Squadron. I was very honoured to do so.

18 June 2007 - Christina Smith (née Bone) writes: Thank you to the Association for the information you supply on the Internet. I wanted to try and find out about my uncle [Henry Bone] who was killed in WW2. I cannot tell you how pleased I was to find the information on the Whyte crew, which answered a lot of questions. For quite a time it did not register that in looking at the photo of the five graves I was actually looking at my uncle's grave. Quite a shock but an added bonus.

Henry Bone was my late father's eldest brother. Unfortunately my father died some time ago and so never realised his ambition of finding out the details of Henry's death. I hope one day to go and place flowers on Henry's grave on my father's behalf. I have also found out about the memorial in Leicester Cathedral.

Flt Lt Jimmy Wardle DFM and the Whyte crew: Friend member Mrs Bev Wardle has a bombing certificate showing a drawing of a Lancaster [she told the editor that James Wardle DFM 148099, 207 Squadron flew with Sgts Mallet, Whyte, Tillon, Eyre, Mason, and Simister on a flight to Italy.Bev has a drawing of a Lancaster and some bombs dropping with the names of the above on them].

Raymond Glynne-Owen, Air Britain Spcialist on 207 Squadron and Honorary Member wrote to Bev: Your enquiry seems to be on the late 1942/43 period, when [James Wardle] flew as a Sergeant Air Gunner with 207 Squadron and Whyte was his regular pilot. The drawing you refer to sounds like a bombing certificate that was awarded to crews during the midwar period when they had shown that they had successfully bombed their designated target. According to the records Jimmy Wardle left 207 Squadron on 24 February 1943. Jimmy Wardle returned to 207 as Gunnery Leader on 5 June 1944, then a Flight Lieutenant.

In the Spring 2012 issue of Memorial Flight, the journal of Lincolnshire’s Lancaster Association, this article appeared about the loss of John Whyte’s crew (EM-M L7547) on an operation to Milan from Langar. Five of the crew were killed and lie in the Communal Cemetery at St Brisson. On 7th May 2005 a memorial was unveiled near the village in memory of the crew, at which flowers were laid on behalf of the Association. There is a page about this crew in the Memorial section of our website.

The editor is grateful to Ron for permission to use his article, which has been slightly edited. His cousin was Sgt Frank Tillen, the Navigator.

TWO CAME HOME

On the night of February 13/14, 1943, 142 Lancasters were dispatched to bomb targets in Milan in the industrial north of Italy.

There was little cloud cover and visibility was good. Fires in the target area were seen 100 miles (160km) away. No. 207 Squadron sent nine aircraft, two did not reach the target and one, Lancaster L7547/EM-M was listed as 'failed to return'.

The log for Lancaster L7547 shows that it had been flight-tested during the day of the Milan raid and was deemed serviceable for that night's duties although the ground crew had warned that: "the engines were dirty". It was being worked on immediately prior to the scheduled take off and was only just ready in time.

It was the squadron's reserve aircraft that night but apparently 467 Squadron [at Bottesford] could not supply all of the aircraft it had been scheduled to use that night. [Editor: For the raid three of 207's 9 aircraft taking part took off from Bottesford, including Whyte in L7547/M] One of [467’s] aircraft had become bogged-down on the taxiway and perhaps this was the reason that L7547 was taken from reserve and put into service at the last minute.

Its take-off time was 19:14 rather than the planned 19:00 and the pilot would probably have tried to make up lost time to join the main bomber stream.

John Whyte: Arriving ‘home’ on Feb 10 1945 he was given 2 weeks sick leave before returning to fly with the RAF. Later commissioned, he did 20 sorties with 50 Sqn between May 26 and July 4. Demobbed in Oct 45 as Flt Lt he sailed back to NZ taking his brown ‘Resistance issue escape overcoat with him.’ |

That night L7547's crew were mostly very

experienced, especially the pilot, Flight Sergeant John Whyte,

who had flown 28 sorties since June 17, 1942.

The aircraft had already completed 14 previous trips. It had a typically multi-national crew comprising an Australian, a New Zealander and five from Britain. Some of them had flown together before but one, Sergeant Harry Bone, was new. Those detailed to take part in that Milan raid may have viewed the target as a relatively 'good one' because the air defences over Italy were lighter than those encountered over Germany and, just the night before, they had attacked the U-boat facility at Lorient which was known for its heavy flak defences. This trip was supposed to last under ten hours and cover a distance of about 1,860 miles (2,993km) at a speed of 200 mph (322km/h); taking advantage of clear weather and good visibility all the way to and from Milan. Over occupied France the starboard outer engine began to overheat and had to be throttled back. At this point the pilot could have been be excused for returning to base and aborting the mission. There are several possible reasons why he may have decided to continue. A Lancaster can function on three engines, albeit more slowly, but this faulty engine was still providing some thrust. Just as importantly though, aborting a mission might be considered as evidence of a Lack of Moral Fibre. Despite being weighed down by fuel, a full bomb load and a faulty starboard-outer engine the aircraft nevertheless climbed to 16,000 ft (4,876m) to cross the Alps. There is no record of the aircraft intruding into Swiss airspace, but it was the practice of some RAF crews to take the short-cut over the Alps to get to and from Italy and the British Embassy in Switzerland did receive complaints about RAF bombers violating Swiss neutrality that night. |

On arrival over Milan, because of the one poorly-performing engine, Flt Sgt Whyte decided to bomb from high altitude rather than the designated 8,000 ft (2,438m). He stayed high because there was a risk that he might not be able to gain enough altitude to get back over the mountains on the way home. The crew probably had to allow an extra time-delay for the additional height in taking the obligatory photograph of their bombs bursting.

Without those photographs the operation could be considered incomplete and may not count towards the crew's score of operations. Although some flak came near to the aircraft the pilot considered that there was no damage and they joined the stream of aircraft for the flight home.

So far, so good.

Return Leg

They were about three-quarters of the way into what should have been a nine-hour flight and yet it was 23:30 hours GMT so that their flight time was only four and a half hours. This supports the theory of flying over Switzerland on the way to and from Milan. About 75 minutes after leaving the target, without any prior warning, the aircraft developed a fire in the port-outer engine - not the starboard outer that had proved troublesome earlier.

Flames were seen coming from the underside of the engine's cowling and, at first, this did not seem too serious, but the integral on-board Graviner fire extinguisher system proved ineffective. By this time the aircraft was near Dijon in France. Flt Sgt Whyte put the aircraft into a dive so steep that its airspeed was thought to have exceeded 360 mph and, as a result, the Perspex canopy caved in. The fire continued to spread and the aircraft was doomed.

After telling the crew to prepare to bail out Flt Sgt Whyte gave the order to leave and this was acknowledged. The bomb aimer, Flt Sgt Strong, was seen to exit first through the front escape hatch followed by the Flight Engineer, Sgt Eyre. The Navigator, Sgt Frank Tillen, was seen to go towards the rear and W/OP AG, Flt Sgt Grainger, seated behind the navigator, would have been expected to make his way forward.

The gunners also had to make their way forward. Sgt Bone, the mid-upper gunner, said on the intercom that he was about to bail out. He was the last crew member to speak to the pilot; probably because they had all disconnected themselves from the intercom system.

John Whyte assumed his crew had jumped and trimmed the aircraft so that

he too could escape, but it lurched so he returned to his seat to try to

reset the trim. He was unsuccessful but, in the next moment, he was

somehow thrown clear. Remarkably, his parachute opened.

The Lancaster crashed near St Agnan, France, in the forest near a farm

hamlet called Les Merlins of L'Etoule de Rupt in the Parc de Morvan area

of Burgundy.

Pilot John Whyte later recalled: "I came down about midnight in hilly country near St Brisson. After hiding my parachute and flying kit I met my flight engineer, Sgt Eyre. We went into some woods and hid for the remainder of the night.

The Last Crew of L7547, Milan, February 13/14 1943

Pilot

|

Flt Sgt John Whyte RNZAF Sgt Frank Tillen Sgt Stanley Eyre Age unknown 22 prior ops Flt Sgt Thomas Strong Flt Sgt Richard Grainger RAAF Sgt Harry Bone Sgt Kenneth White |

Age 26 Age 27 Age 27 Age 27 Age 29 Age18 |

28 prior ops 17 prior ops 6 prior ops 20 prior ops Unknown ops 7 prior ops |

Stanley Eyre made the Royal Air Force his career, was awarded the DFC and MBE and retired with the rank of Squadron Leader. |

The next morning we met two Spaniards on the road

and asked them for help, but they could not do anything for us.

"A little later we came across another Spaniard burning charcoal

in the woods. He took us to see a Frenchman, who in turn took us

to a house on the outskirts of St Brisson. We spent two or three

days there and, from this point on, our journey was arranged for

us."

Flight Engineer Stan Eyre also survived the jump and later he recalled, "I came down near St Brisson. After burying my parachute and flying kit I started walking. About two hours later I met Flt Sgt Whyte." Though they didn't know it yet, the other five members of their crew - including my cousin, navigator Frank Tillen, were dead. These accounts do not exactly match that given by André Bouquin, the first Frenchman to help them. It was he who got them food and civilian clothes and passed them over to the members of the Resistance on that first day. However André Bouquin's notes were written in 1946. Even so, my family's research has been able to verify much of his account and the differences are insignificant. It isn't too surprising that the airmen encountered Spanish loggers. Many Spaniards escaped from Franco's Spain after the Civil War. Some of them were Communists and indeed the French Communist party was strong in the area and would have supported them. As Republican escapees they were probably illegal immigrants and, therefore, very anxious to escape the notice of the Germans occupying that part of France. If caught they would be interned as political prisoners. Alternatively, if caught, they may have been forced into the foreign equivalent to the Compulsory Labour Service, the Compagnies de Travailleurs Etrangers or CTE. The CTE permitted foreign prisoners to leave the internment camps if they would go to work in factories in Germany. Young Frenchmen were also in danger of being forcefully conscripted into German labour camps. Parc de Morvan is a heavily forested and remote part of Burgundy. It was a good place to hide out and not be noticed. |

Help arrives

Phillipe Senac, a French aviation historian, who has investigated the whole incident, relates that the airmen went to an old barn where they met with members of a Spanish family of loggers called Barbero Henrandez who were living there.

In spite of the language difficulties the airmen became aware that the Spaniards were at risk to themselves if they were caught aiding the airmen and were considering turning them over to the Germans. Evidently this was an attractive alternative because they might be eligible for a 1,000 franc reward. The airmen decided to leave and walked back along snow-covered paths into the forest until finding a charcoal burner's hut where they were apparently warming themselves when André Bouquin and Emile Burbaud walked in and found them.

Long after the event other members of the community recalled that the Spaniards had really intended to hand the airmen over to the Germans.

The French account of the Crash

André Bouquin was a young man who had just turned 18 when L7547 crashed. He worked at a local petrol station and in all other respects was leading as ordinary and peaceful a life as would be permitted during the Occupation. In 1940 he had already anticipated that there would be resistance against the German occupiers and had hidden weapons and ammunition abandoned by the French Army.

He went on to become active in the Resistance and later joined the local Maquis Bernard group with the code name Casy. In 1946 with war over he did his national service in the French Marine. With spare time on his hands André wrote his account of what he called My First True Mission. Our literal translation of his idiomatic French isn't perfect but the story he tells is so compelling that it's absolutely essential to understanding what happened next.

After the war André Bouquin became an artisan, married and lived in the nearby town of Salieu. He died in 2004. We were too late to meet him and missed an opportunity to talk to a participant in the escape of the two airmen and the bad times that followed.

"That night of Sunday February 13 we were awakened by the roar of about one hundred airplanes coming back from a raid on Southern Germany or Northern Italy. We had become accustomed to such a noise and we often went back to sleep after the planes had gone by – normally there two waves, one going out and the other returning. This time, after the sound diminished, we heard another, but unusual one, which grew louder and louder and closer and closer. My mother said "Are you asleep?' "No, why?" I replied. She answered, "You heard - what was it?" "A plane that revved its engines," I replied. The noise went away slowly, then nothing more.

That Monday morning, as every day, I went to see Mimille (my cousin Emile's nickname) who lived above the garage opposite my uncle's café. We went to the woods. On the way, of course, we talked about the noise from the planes of last night. Mimille said that he had stood up to look outside and it's seemed to him that one of the plane's engines was on fire. Then he added: "It probably crashed not far from here, just after its crossing above Saulieu, but I did not hear it."

We arrived at the old mill of Chailloux, parked our bikes and walked up the path. In sheltered places, the snow had not melted completely. Mimille remarked that there were tracks that were not there on Saturday or Sunday and if they had been there that he would have seen them.

"What has made tracks in this corner? Who could have loafed around?" he asked "Perhaps guys came to set up snares" I replied. I noted that there were two tracks, then no more snow, the tracks disappeared and we thought no more about it.

When we arrived in sight of the hut we were very surprised because smoke was coming out of the chimney. We stopped; my friend thought there might be prowlers inside and I thought there may be escaping prisoners. As a precaution we armed ourselves with a big piece of wood and each went to one corner of the hut.

The door was ajar. I pushed it with my foot and we stood at the opening with our bludgeons in our hands. A voice cried, "NO, FRIEND, NO." We went in and found two guys in uniform. We realised that they must be English airmen. They tried to explain and we tried to understand. It was not easy, they spoke only a few French words and Mimille only knew a few words in English. I said nothing.

By gestures they made us understand that their aircraft had passed over the German anti aircraft battery in Dijon. They said that it had crashed about one hour's walk from here and that five of their companions were killed. Mimille appeared sceptical; I could see by his behaviour that he was concerned, so he spoke to me in the local patois.

"What if they are Germans disguised. Do you believe them?" "I will go

to the crash site and see"

"Go if you want to. I will keep them here. "Perhaps they have the

clothes as a disguise".

"You are an idiot to talk in patois they can't even understand French"

"But if they are the Boches ... ?"

André Bouquin's account continues: "I walked down to the mill, took my bike and cycled towards Eschamps. If the plane had fallen in that area, Father Emery and his son (also named André) would be able to confirm it. When I arrived at their house they asked me what I was doing in that vicinity.

I explained that I had heard a plane in the night, and I wanted to know if it had crashed in the neighbourhood. They told me it had come down near the hamlet of Les Merlins. They had woken up and had seen it fall but they hadn't been to see exactly where yet. I started off in the direction of St Agnan, turned left to L'Etoule du Rupt and arrived at Les Merlins.

The local people of the hamlet were 'excited' and were all talking about the plane. Two men decided to go and reconnoitre the crash site and I followed them. They knew the woods well and clearly knew what direction to take. We walked up though the woods and, judging by the sun, I thought that we were heading in the direction of St Brisson.

Suddenly we saw a wreck, and we approached it. It was horrible. We discovered five dreadfully mutilated bodies."

Discrepancy

Despite this statement André could only have seen four bodies at the time because Flt Sgt Strong's body was found buried up to his waist some way off in the hamlet of Loisins. Although he had jumped from the Lancaster first, his parachute had not opened. It seems unlikely that André or the two evaders would have known this until a while later.

In 2008 when we talked to Alexis Cordin, a retired former mayor of Champeau, he stated that local people had seen the aircraft "spewing flames” as it came down and that this had caused fires on the ground. The aircraft and its crew members that descended by parachute all came to earth within a few miles of each other, so it seems probable that the Lancaster descended in a tight spiral. It appears that five of the crew did jump and that three parachutes did not open; or at least not in time to save the men.

André's account continues: "The younger of my two guides vomited and ran away. The older man, who was a veteran of 1914-18 war, grew pale, but stayed very calm. I have to confess that my stomach was upset, but I put on a brave face. Two bodies lay mangled in the fuselage. We found a parachute caught up in a tree. There were also the bodies of two men that had tried to use their parachutes. One had been 'scalped' while the other was impaled on a branch. We looked around to see if there were any other bodies. There were tracks in the snow that were joined by another set further away. My companion told me that two other crewmen had escaped and that, although he had seen this, he would say nothing. Further on the snow had melted and we lost the tracks.

We hardly spoke as we went back to Les Merlins. I didn't know what he was thinking but for my part I knew what to do. When we got back to the home of Father Emery and his son André they invited me in but I knew that I must not tell them what I had seen. Monsieur Emery offered me a Goutte [a fiery local spirit] to calm my nerves, which I gratefully accepted. I then left under the pretext that I had work to do."

Escape Line

German soldiers recovered the bodies of the five dead airmen and, noting that two were missing, questioned the local villagers about what had happened to the survivors. Apparently, nobody had seen any survivors ... though soon afterwards the airmen’s location was nearly given away by a local postman who was thought to be after the 1,000 franc reward available for their capture.

A Luftwaffe officer, part of the team sent to inspect the Lancaster's wreckage, gave the church his permission to bury the dead, on the understanding that the priest would deliver a benediction with only the local mayor of St Brisson present.

On the day of the funeral, another significant snowfall had blocked the country lanes leading to the church, thereby preventing the German military from attending. As a result, the church was full for the funeral. A makeshift Union Jack, made by an unknown hand, was placed beside the coffins. Each was covered with flowers – not an easy thing to arrange in February.

Unhindered by German observers, the village priest conducted a full funeral service followed by a sermon. All those that attended the service then followed the coffins to pay their respects as the airmen were buried in St Brisson.

On the run

The two surviving young airmen were very lucky. Not only had Stan Eyre and John Whyte escaped a close shave with death, they were also fortunate enough to be found by some very brave French civilians who risked everything in order to give them the chance to return to the fight.

After each was given a set of civilian clothes that didn't fit too well (they were all that was available), their RAF uniforms were burnt. The exact details of their return route are not know but a combination of the evaders' reports and later research has enabled a significant amount of detail to be acquired.

Doctor Chevillotte, Mayor of St Leger Vauban and a member of the Resistance, looked after one of the two airmen. Father Mayeul remembered that one of the airmen had a bad ankle but this was not much of a handicap. Estimates about how long the two airmen spent at the Abbey vary from two days to at least a week while the Rev Ferrand organised their escape.

They were hidden in a part of the Abbey that had an easy escape route to the forest in case the Germans arrived unexpectedly.

The Abbey print shop probably made their false identity cards. Stanley Eyre became Louis Darnet, born September 19, 1916, in Nîmes, while John Whyte became Louis Herbot, born November 1, 1917, at Lille. Several members of the Roman Catholic Church were involved in helping the airmen along their escape route.

At least one source states that the two flyers were taken first to Avallon, then Paris, but it was a tortuous route as, after travelling all that way north, both were then sent south again, ultimately heading for Spain and then Gibraltar.

According to French sources the two airmen were taken from Paris to Annecy in the Savoy area of France. It is close to the French-speaking part of Switzerland and, ironically, it was also the area that their Lancaster should have flown over on their way to and from Milan. A children's settlement centre in L'Yonne lies within the mountain pass of Tame near the Abbey of the same name.

Stan Eyre and John Whyte at a safe house

Starting from this pied-a-terre in Savoy, links were established with the Resistance of the Armée Secrète (AS) and in particular with Jean Carquex, known as Milleau, who was responsible for the AS in that part of Faverges. At one time, both airmen were temporarily hidden in the home of Mr and Mrs Joseph Simon, an insurance agent in Faverges.

Sometime during March 1943 they received a visit from the Special Operations Executive's (SOE's) Peter Churchill who variously used the names 'Michel' or 'Raoul'. After parachuting into France [together with his female radio operator, the now legendary secret agent Odette Sansom GC, LdH, whom he later married] that month, Peter Churchill ran SOE's Section F, in the south of France. During his visit Peter Churchill was accompanied by a man known only as 'Riquet' and the network's radioman, Captain Rabinovitch, known as 'Arnaud', who was able to inform the British authorities of their situation.

However, the news of their presence was spreading rapidly in Faverges so, to protect their security, the airmen were moved to the home of Mr and Mrs Durbet, another insurance man, living in Annecy. The transfer took place two days before their passage to Switzerland in March 1943.

Both airmen were guided by a man and young girl whose identities are

not known.

As researcher Phillipe Senac has discovered, the airmen were led to

Berne in Switzerland but whether this was by sneaking across the border

or by the use of forged passports is not clear. As the two flyers could

barely speak any French or German it seems likely that they gained entry

via an unofficial route because Switzerland didn't always welcome

escaping Allied airmen.

By late March, somehow, word had reached England that two members of the crew of Lancaster L7547 were no longer missing; had survived a crash and were safe in Switzerland. Frank Tillen's mother (my aunt) got to know this and wrote to W/Op AG Flight Sergeant Richard Grainger's wife in Australia on April 21, 1943 to ask if she had any news.

Dear Mrs. Grainger,

I am the mother of Sgt Frank Tillen who was navigator in the same plane in which your husband was reported missing.

Tonight I have heard from another member of the crew's wife, that Mrs Eyre, wife of Sgt Eyre, has received a cable saying that her husband is safe and well in Switzerland and I am wondering if you have received similar news. Do please let me know if you have any as I am so terribly anxious about my son. You will understand my anxiety when I tell you I have already lost my youngest son who was also a navigator.

Hoping to hear from you soon I remain.

Yours sincerely

Mabel A Tillen.

It is hard to read that letter and not be moved. The anguish is all too apparent. Although Mabel didn't know it yet, no good news would arrive. Two of her three sons died flying with the RAF. At the time of his death Frank Tillen was engaged to be married to a local girl called Gwen but we do not what became of her.

'Stewie' Grainger, the son of L7547's W/OP AG, Flt Sgt Richard Grainger, mailed my aunt's letter to me from Australia in 2007. 'Stewie' was born during the night that his father was over Hamburg. He feels that his mother did not receive the sympathy and support she deserved from the authorities after his father's death and there is still some bitterness there all these years later.

62 years after the event, a memorial was unveiled adjacent to the crash site [see top of page].

The two RAF evaders were lucky to have been well-treated in Switzerland. Sergeant Eyre and Flight Sergeant Whyte were allowed to 'escape' from Switzerland but they had to leave separately. Once back over the border the plan was to use trains and buses to cross Vichy France to get to Spain and then get home via Gibraltar.

On January 8, 1944, Stanley Eyre was assigned to an escape party led by RAF Squadron Leader Fletcher Taylor of 425 Squadron. The group comprised two Americans, five British and one Canadian. On entering France members of the Resistance guided them to safe houses ready for the risky journey to the Pyrenees mountains.

Unfortunately the Germans had stopped all civilian rail travel in reprisal for Resistance attacks on some German officers. As a result the group had to stay in the village of Frangy in the Department of Haute Savoie for a month.

Stanley Eyre stayed with the same family as a 22-year old American flyer, Second Lieutenant Warren Carah, who had been shot down over Le Mans on July 4, 1943. For the journey across France they were again split up into less conspicuous sub-groups, each accompanied by French guides.

From Frangy, Savoie, Stanley Eyre's group made their way to Perpignan near the Spanish border via Lyon and Marseille before a Catalan guide took them over the mountains into nominally-neutral Spain on February 5, 1944. Stanley Eyre reached British Gibraltar 18 days later. He was flown home on a RAF Dakota, arriving back in the UK one year after surviving the crash.

Not so lucky

Even though he had left Switzerland several weeks ahead of Stanley Eyre, pilot John Whyte was not so lucky. It was cold and the Resistance had given him a thick brown overcoat. John wore this coat while travelling on a train through the south of France when a German officer sat next to him. John sat sweating in a state of nervous tension, not daring to speak or draw attention to him. After reaching the Pyrenees he slipped and fell while evading capture as his group crossed the border into Spain. He hurt his chest quite badly, leaving him with an injury that troubled him for years to come.

Flt Sgt Whyte passed through the French-Spanish border and was subsequently arrested and taken into custody in the town of Figuras, where he took on yet another false identity, that of John Green, 'a New Zealand-born soldier that had accidentally passed into Spain'. Because of his chest injury he was admitted to a hospital for a while. Official records show that the doctor released him to the police in good health and "free of parasites".

After being released from hospital John passed through several towns' police stations, sometimes imprisoned and sometimes put in hotels, labelled as an "accidental visitor" who had entered Spain illegally. Finally, he was sent to Gibraltar via Madrid, arriving there on February 7, 1944. The RNZAF sent a telegram to notify his wife on February 11 and, a few days later, she received another signal announcing his return to England.

Upon arriving back in Britain the two evaders were debriefed and their typed statements were classified as secret to protect the brave members of the French community from potential persecution. Both airmen were later commissioned.

Arriving 'home' on February 10, 1945, pilot John Whyte was given two week's sick leave before returning to flying duties with the RAF. Between May 26 and July 4, 1945, he completed another 20 sorties while flying with 50 Squadron. In October 1945 he was de-mobbed with the rank of Flight Lieutenant and sailed back to New Zealand. The brown overcoat went with him.

During their under-cover escape, one of the airmen, wearing civilian clothes, was guided by Abbé Ferrand, Arch-Priest of Saint Lazzarre D'Avalon who was a well-known Resistance worker. He was eventually arrested by the Gestapo and died in its custody a month later.

Before the invading Allied armies were able to finally drive the Germans from France, several villages located near to where Lancaster L7547 crashed suffered German reprisal raids. These resulted in the on-the-spot executions of some 30-40 local men that were suspected of being 'terrorists' and atrocities were also committed against some of the villages' women and children.

There is an enduring mystery about the identity of the priest who conducted the service at the funeral of the five airmen killed when L7547 crashed. Today’s villagers believe that the Priest was an Englishman - or that he at least spoke fluent English. They say that he left for London when the war ended. Navigator Frank Tillen's brother is amongst those that have tried to trace him without success.

Post-war, André Bouquin (who helped Stanley Eyre and John Whyte to escape - and upon whose testimony much of this story is based) was honoured for his resistance work with several awards; France's Cross of Combat Volunteer 1939-1945, the Medal of the Resistance, the 1939-1945 Commemorative Medal, the Medal of Recruits, the Victoria Medal and the Recognition of the Nation title. On Friday, August 29, 2004, his family honoured his wish for his ashes to be buried amongst those of his former Maquis Bernard resistance fighters.

In St Brisson, the graves of the five airmen were tended by the villagers. After the war the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) erected the five headstones that mark them today.

The Forces Francaise de L'Intereur (FFI) has also placed a memorial plaque made of white stone in memory of their wartime comrades. I with several other members of the Tillen family, have made the pilgrimage to Frank's grave and on each visit we have seen a fresh wreath there, placed by the FFI.

In May 2005 the villagers erected a memorial in the forest very close to where the Lancaster crashed. Photographs and details of the dedication may be seen on 207 Squadron Association’s website.

The engines were removed from the crash site a long time ago and by 2008 the remaining pieces of the bomber had either been salvaged or decayed to the extent that nothing obvious could be seen in the luxuriant mosquito-infested undergrowth. By using a metal detector and scraping the ground with a rake and a hoe it is still possible to find tiny remnants of the aircraft. We found small flaky pieces of metal sheet and pieces of screened cable.

With Pat Hunt's help we identified tiny fragments of the textile fabric that was used to line fuel tanks. The French Government now considers World War Two crash and battle sites to be of archaeological and historical importance so 'scavenging' and the removal of relics is forbidden, but clearly this has not been taken too seriously in this case.

In addition to the CWGC-recognised cemetery containing our Frank's grave, we also visited the graveyard at Ouroux where André Bouquin and some of his fellow Maquis Bernard Resistance members lie. It sits on a remote forested hilltop and also contains memorials to the crew of another RAF aircraft that crashed nearby while on a supply mission and members of the British Special Air Service.

It is a quiet, isolated, place that offers a powerful evocation of those terrifying last few months of the war. We visited the site during a torrential downpour accompanied by thunder and lightning which added to the atmosphere and our feeling for the sacrifices that had led to the creation of this memorial.

In the church near Langar airfield {St Andrew’s, Langar] where 207 Squadron was based when 'our' Lancaster started its ill-fated journey, there is a wall-mounted memorial [and Book of Remembrance] to the 251 men that were killed flying with the unit from February 1942 to October 1943.

This Roll contains the names of 251 personnel who gave their lives whilst serving with 207 Squadron, RAF Langar, September 21st 1942-October 13th 1943.

[Members will recall that we also have a memorial close to an entrance to the airfield at Langar. The airfield is still in use as a centre for recreational parachuting and training. We are grateful to the team of Friend members who maintain the memorial. In March 2011, close by the airfield memorial, a special plaque detailing the airfield’s history was unveiled by John Whyte’s son, John]

The memorial was dedicated in 1994 and again ten years later. The

descriptive plaque can be seen on the left.

The seat was among many generous donations to the Association by the

late Mrs Dorothy Ware

whose first husband Tom Skelton was lost from Langar.

Contact was made with a niece of the mid-upper gunner, Sgt, Harry Bone, but no other crew members' relatives have been traced. In the last few years the sons and daughters 'of L7547' and members of the Resistance have made an effort to ensure that the wartime sacrifices made by their parents are not overlooked by the next generation.

Veterans of 207 Sqn and members of the FFI are a vanishing breed; they are now all in their eighties or nineties. The snow-covered path along which John Whyte and Stanley Eyre took their first steps towards freedom on a freezing February day is now a hiking path and I think it is remarkable that the crash-site memorial was erected 62 years after their 5 comrades died.

As the post-war generation has also reached retirement age, they are now making the effort to travel to France from New Zealand, Australia, the USA and Britain to pay their respects; honour and learn from the surviving witnesses of the last terrible years of wartime, all of which should serve to ensure that we shall remember them.

The graves of the five men lost with Lancaster L7547. Sgt Frank

Tillen’s grave is on the right

With thanks to Ron Tillen for permission to make use of this material.

Philippe Sénac has written:

HISTOIRE DU LANCASTER L7547

Dans la nuit du 14 au 15 février 1943, un bombardier anglais s’écrasait dans la forêt située à quelques kilomètres du village de Saint Brisson (Nièvre). Après de nombreuses recherches, je peux maintenant reconstituer une partie de cet événement.

LES HOMMES

L’équipage était composé de sept membres, deux eurent le temps de se parachuter, les cinq autres eurent moins de chance et périrent dans le crash de l’avion. A l’époque, des témoins affirmèrent que certains avaient sauté d’une altitude trop basse ne permettant pas l’ouverture complète de leurs parachutes.

Les deux survivants sont le pilote et le mécanicien :

Flight Sergeant WHYTE John Henry Francis (Royal New Zealand Air Force) /

Pilote

Flight Sergeant EYRE Stanley Herbert (Royal Air Force) / Flight Engineer

(Mécanicien)

Les deux aviateurs se sont réfugiés à l’Abbaye Sainte Marie de La Pierre qui Vire (Yonne), située à quelques kilomètres des lieux de l’accident. Ils ont été pris en charge par le père Wulfran Jeanne qui conduisit lui–même un des sergents à Paris. Le second fut hébergé par l’Abbé Ferrand, Archiprêtre de St Lazare d’Avallon (Yonne). Le F/Sgt EYRE rejoignit l’Angleterre après un périple de plus d’une année puisqu’il atteindra l‘ Espagne.Il réussit son évasion en passant par le canton de Berne (Suisse) qu’il quitte le 8 janvier 1944 en compagnie de 8 autres évadés (4 aviateurs anglais, 2 américains et 1 canadien) et rejoindra Barcelone le 16 février 1944, en passant par Frangy (Hte Savoie), Lyon, Marseille, Perpignan. Le sort du pilote n’est pas connu mais il serait rentré également en Angleterre en passant par l’Espagne.

Les cinq autres membres de l’équipage ont été enterrés dans le cimetière communal de Saint Brisson (Nièvre):

| Tombe n°1 Flight Sergeant STRONG,

Thomas William, 27 ans Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, service n° 1114468 Observer (Observateur) Marié à Eléonor Joyce STRONG BLYTH (Northumberland, Angleterre) |

Tombe n°4 Sergeant WHITE, Kenneth

James, 19 ans Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, service n° 1535795 Air gunner (Mitrailleur) Fils de Percy et Florence Annie WHITE SOUTH SHIELDS (Co. Durham, Angleterre) |

| Tombe n°2 Flight Sergeant GRAINGER,

Athol Richard, 27 ans Royal Australian Air Force, service n° 403169 Wireless Operator (Radio) Fils de Reynold Bede et de Margaret Ann GRAINGER Marié à Margaret Rennie CRUIKSHANKS - GRAINGER LISMORE (New South Wales, Australie) |

Tombe n° 5 Sergeant TILLEN, Frank

Ivan, 27 ans Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, service n°1175445 Navigator (bomber) (Navigateur – bombardier) Fils de Franck et Mabel Alice TILLEN BASINGSTOKE (Hampshire, Angleterre) |

| Tombe n° 3 Sergeant BONE, Henry

George, 29 ans, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, service n° 1381738 Air gunner (Mitrailleur) Fils d’ Henry George et Harriet BONE BEDFONT (Middlesex, Angleterre) |

[* in fact according to Sgt Eyre's and F/S Whyte's debriefing reports F/S Strong was Air Bomber and Sgt Tillen was Navigator: Sgt White was Rear Gunner and Sgt Bone was Mid-Upper Gunner] |

LA MISSION

Au début de l’année 1943, le commandement anglais a planifié des raids contre les villes de l’Italie du nord. Dans la nuit du 14 au 15 février, 142 Lancasters appartenant aux 1st, 5th et 8th Group conduisent le premier raid massif contre Milan. Cette ville avait été attaquée une première fois le 24 octobre 1942, elle le sera de nouveau et de façon plus intense en août 1943.

Le 207 sqn fournira pour ce raid 9 appareils, 3 devaient faire demi-tour et un seul ne revint pas (le L7547). Cette mission devait durer environ 10h (3000 km à une vitesse de croisière de 330 km/h). Au retour d’Italie, le moteur extérieur gauche prit feu suite à une surchauffe. Un deuxième Lancaster fut aussi porté manquant au cours de cette sortie.

L’AVION

AVRO type 683 LANCASTER BI Serial L7457 construit en novembre 1941 par

AV Roe Co. Ltd. à Newton Heath (Manchester,UK)

Affecté au A Flight du 207 squadron "SEMPER PARATUS" (“ALWAYS PREPARED”

- "TOUJOURS PRÊT") (5ème Groupe)

Code EM-M

Basé à LANGAR ( Nottinghamshire ) Pundit code : LA

Heure du décollage : 19h14 GMT le 14 février 1943

Heure approximative du crash : le 15février 1943 vers 2h GMT (1500km

entre Langar et Milan + 650km entre Milan et St Brisson) soit 2100 à

2200km à 330km/h de vitesse de croisière (environ 6h30 de vol)

Total heures de vol : 208 h (au dernier décollage)

HISTOIRE DU LANCASTER L7547

Cet avion a été fabriqué à partir des cellules d’une série de 200 AVRO Manchester IA, dont la construction venait d’être abandonnée. Le Lancaster reprenait une grande quantité de pièces à son prédécesseur en particuliers le fuselage auquel une nouvelle aile équipée de 4 moteurs Rolls- Royce Merlin type XX de 1280 ch. Il appartient au premier lot dont le serial va de L7527 à L7549.

Vers la fin de l’année 1941 ou au début 1942, il est affecté au 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron, A Flight, basé à Waddington (Lincolnshire, Pundit code: WA) où il est codé KM-D (for Dog). Après une période d’entraînement de 3 mois, le L7547/D participa à la première mission de guerre d’un Lancaster. Il s’agissait d’une opération de minage dans le secteur des îles Heligoland au Nord-Ouest du port de Bremerhaven (Allemagne) ( Opération « Gardening », secteurs YAMS et ROSEMARY ). Il était accompagné de 3 autres Lancasters (L7546/J ,L7549/Q et L7563/W) et était piloté par le W/O LAMB N.P.J.. Ce pilote participera aux attaques contre le cuirassé allemand « TIRPITZ » en avril 1942 et devait disparaître le 8 mai 1942 au cours d’un raid sur Warnemünde (Allemagne).

En septembre 1942, il rejoignait le A Flight du 207 sqn et devint le EM-M (for Mother) Il était le 21ème d’une série de 7037 Lancasters construits de différents modèles. Ils effectuèrent 156192 sorties (le 207 sqn : 4100 environ) et larguèrent 608612 tonnes de bombes, 3836 furent perdus, En moyenne chaque Lancaster a effectué : 27.2 sorties et larguer 154t de bombes.

Seuls 35 Lancasters atteignirent le nombre de 100 missions …

STATISTIQUES DU 207 SQUADRON

Pendant la période du 24 avril 1942 au 25 avril 1945, 277 Lancasters B I ou B III ont été pris en compte au 207 sqn, 177 avions furent perdus (75 au A Flight, 72 au B Flight) et 851 membres d’équipage perdirent la vie. L’ordre de bataille du 207 sqn était de 16 à 18 appareils au début 1943 et fut porté à 20/21 en 1944.

Au cours de la seconde guerre mondiale, le RAF Bomber Command perdit

47268 aviateurs :

51% tués en action dont 88% portés disparus

9% tués à l’entraînement

12% des survivants furent fait prisonniers de guerre

3% seront blessés et mis hors de combat

1% des survivants évitèrent la capture

25% terminèrent leur tour d’opération (30 missions)

Links

Commonwealth War Graves Commission - Saint

Brisson Communal Cemetery (the individual graves are

detailed from this link via Cemetery Report).

St

Brisson, Nievre tourism

Report on Le

Bien Public (in French)

Google Maps (enlarge to locate the village) - St

Brisson

207 Squadron RAF History

page last updated 6 August 2013: 18 Nov 17: 13 Jan 19 and more to

be added